Is it December already?

I recently visited Murakami Naval Museum in Shikoku, Japan, as part of my research on medieval navies.

Japan used to be subdivided by Samurai lords. If you are watching international news, you'd have noticed the recent accident in a motorway tunnel, in which the ceiling of a tunnel collapsed, killing at least 9. Japan is a mountainous country, so if you travel in japan, there are so many tunnels.

In the medieval period, when there was no technology to bore stable, usable tunnels, it was easy for local elite to maintain a degree of independence, rejecting interference from central government. As a result, there were many mini states ruled by local warrior lords who ran their own domains as if they had been proper states. As a matter of fact, the Japanese word for provinces is the same as state or country, even though, today, they are called prefectures.

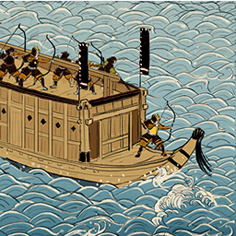

Those who was in a position to dominate coastal waters built strong fleets to conduct business in sea transport and fishing. In time of domestic war, they would offer their fleets as fleet auxiliary to any warring factions. They could also act as pirates and land raiders, attacking their enemies.

Murakami is one of the strongest such sea lords of Japan in the 16th century. They developed a naval force looking almost modern combat fleet, consisting of battleships, cruisers and smaller crafts for close in combat.

The museum sells romanticised image of Murakami. Some of the Murakami leaders were idolised as the Great Pirate Chief. Apparently, they called themselves pirates just to frighten sailors. They had to, as their business was to regulate waterways in their domain, charging fees to any ship wishing to use them. The cruisers were means to give chase to anyone who tried to run without paying.

I cannot help comparing their naval vessels with Greek and Roman triremes and galleys from the ancient and medieval periods I'm familiar with. Most of these Japanese ships are roughly of the size of the Athenian trireme. The trireme is supposed to be a fast ship, using its momentum as its chief weapon. No wonder the Murakami cruiser type is similar to the trireme, as they were supposed to catch up with toll-runners. Though the Japanese did not usually use ramming tactic. This is perhaps due to confined nature of Japanese coastal waters.

The Japanese would fight from the ship's decks, with arrows and other projectiles. In this sense, their style is closer to that of the Byzantines. It is interesting that when in the west, the Byzantine dromon was slowly giving way to the Venetian galley that would dominate naval warfare in the Mediterranean, there was corresponding development in East Asia too. Naval cannon was also introduced in the 14th century in China; in the west, too, soon the Venetian galley with a cannon mounted at the bow of the ship, instead of Greek fire as on the dromon, would become the standard combat ship type in the Mediterranean too.

In the West, development of naval technology began to accelerate in the 16th century, when the Venetians were duelling with the Ottoman Turks. Soon, ocean going sailing ships would revolutionise naval warfare and maritime commerce. In East Asia, unfortunately, peace descended in Japan and naval warfare and piracy became a thing of the past. This era of naval holiday would end with the ending of the little ice age and the coming of European navies ...

I recently visited Murakami Naval Museum in Shikoku, Japan, as part of my research on medieval navies.

Japan used to be subdivided by Samurai lords. If you are watching international news, you'd have noticed the recent accident in a motorway tunnel, in which the ceiling of a tunnel collapsed, killing at least 9. Japan is a mountainous country, so if you travel in japan, there are so many tunnels.

In the medieval period, when there was no technology to bore stable, usable tunnels, it was easy for local elite to maintain a degree of independence, rejecting interference from central government. As a result, there were many mini states ruled by local warrior lords who ran their own domains as if they had been proper states. As a matter of fact, the Japanese word for provinces is the same as state or country, even though, today, they are called prefectures.

Those who was in a position to dominate coastal waters built strong fleets to conduct business in sea transport and fishing. In time of domestic war, they would offer their fleets as fleet auxiliary to any warring factions. They could also act as pirates and land raiders, attacking their enemies.

Murakami is one of the strongest such sea lords of Japan in the 16th century. They developed a naval force looking almost modern combat fleet, consisting of battleships, cruisers and smaller crafts for close in combat.

The museum sells romanticised image of Murakami. Some of the Murakami leaders were idolised as the Great Pirate Chief. Apparently, they called themselves pirates just to frighten sailors. They had to, as their business was to regulate waterways in their domain, charging fees to any ship wishing to use them. The cruisers were means to give chase to anyone who tried to run without paying.

I cannot help comparing their naval vessels with Greek and Roman triremes and galleys from the ancient and medieval periods I'm familiar with. Most of these Japanese ships are roughly of the size of the Athenian trireme. The trireme is supposed to be a fast ship, using its momentum as its chief weapon. No wonder the Murakami cruiser type is similar to the trireme, as they were supposed to catch up with toll-runners. Though the Japanese did not usually use ramming tactic. This is perhaps due to confined nature of Japanese coastal waters.

The Japanese would fight from the ship's decks, with arrows and other projectiles. In this sense, their style is closer to that of the Byzantines. It is interesting that when in the west, the Byzantine dromon was slowly giving way to the Venetian galley that would dominate naval warfare in the Mediterranean, there was corresponding development in East Asia too. Naval cannon was also introduced in the 14th century in China; in the west, too, soon the Venetian galley with a cannon mounted at the bow of the ship, instead of Greek fire as on the dromon, would become the standard combat ship type in the Mediterranean too.

In the West, development of naval technology began to accelerate in the 16th century, when the Venetians were duelling with the Ottoman Turks. Soon, ocean going sailing ships would revolutionise naval warfare and maritime commerce. In East Asia, unfortunately, peace descended in Japan and naval warfare and piracy became a thing of the past. This era of naval holiday would end with the ending of the little ice age and the coming of European navies ...