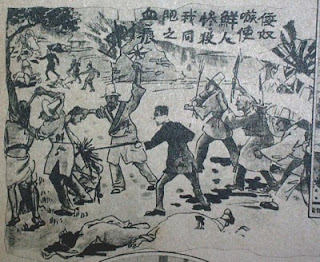

Recently, working on the quake of 1923 that hit Tokyo area in Japan on September 1, I’ve been reading some documents compiled by local governing bodies shortly after the quake. One document dealing with the problem of Korean labourers was obviously written in the wake of frenzied attacks on the Koreans by frightened people in the immediate aftermath of the quake. Those who had lost their homes, livelihoods and loved ones simply believed in unsubstantiated rumours about a large number of Korean workers attacking, robbing and raping people and decided to defend themselves. It is a fair guess that the social research divison of the City of Osaka Council investigated into causes of such atrocity (it is said that up to 2,000 might have been killed) examining actual conditions those Koreans were in.

The document is amazing in its frankness. They do not hesitate to call those Korean workers ‘under-cultured’ or ‘of low intelligence’ as a matter of fact way. No, they add, we’re not saying that Koreans in general are stupid. It’s just that it is the rustic types from the poorest parts of rural, agricultural communities of Korea that wish to come to Japan in search of better material life. We sympathise with them.

But imagine there had been Wikileaks back then, leaking some excerpts from this one. An Egyptian or Libyan style uprising would have followed in Korea in protest, which had just been colonized by Japan. So politically incorrect and racist by our standard, but, one must wonder, was this the kind of language normally used in the early twentieth century?

At best, the document is patronising. It does point out that the widely held prejudice against the Koreans by the Japanese public was unjust and racist. Instead, people should feel sorry for the plight of the Koreans, whose background, oppressed by abusive landowners back home, fostered their rather coarse existence.

The document was written in support of a policy to promote assimilation of the Korean migrants. One researcher said to them something like, ‘You’ve got a crappy job. You’re descriminated against and treated like a slave. Your have no family here. Do you want to go home?’ Obviously one Korean answered, ‘I’ve got a crappy job back home and treated harshly anyway. If so, I’d be better off in this brightly-lit city of Osaka.’ Also the researchers noted that they were too busy and tired even to resent Japan’s colonization of their country. If they could be taught Japanese ways, improve their Japanese and integrate into Japanese society as fully respected members, then, both the good Japanese public and the poor Koreans could live happily side-by-side.

What to make of this document? Maybe they were trying to say that there was nothing racist or imperialist about the policy of assimilation, which was really about pragmatic solution to one problem Japan’s high policy produced internally. (They even state that what they recommended was the most compassionate course.)

This document was published, ironically, when anti-Japanese (together with anti-Chinese and anti-Korean, but especially anti-Japanese) protests were flaring up in the US in 1924. A law limiting immigration from Asia to the state of California was passed. While the Japanese newspapers angrily denounced it as a racist insult, Japanese diplomats admitted in private that they could not complain as they were treating the Koreans in exactly the same way.

Such was the world before WW2. The consolation this time, in the wake of the 3.11 quake in Tohoku, Japan, is that no panic or violence followed. Or, were we lucky that the quake hit sparsely populated regions? (Even so, more than 20,000 have been killed. This tells you how catastrophic this latest quake really was!)

No comments:

Post a Comment